The Acropolis

The Athens Acropolis has the city's most iconic building, the Parthenon, along with other historic buildings and is where the Elgin Marbles were removed from.

Akro poli means 'upper city', and many Greek towns and cities have an acropolis. Athens has the most famous, topped as it is by the Parthenon. Whether you see it in daylight when approaching from the airport, at night from your hotel balcony, or up close when you visit, the Parthenon dominates the Athens skyline, a constant reminder of the Golden Age of ancient Greece.

Sometimes people get confused with the names. The Acropolis is the whole area of the upper city, and the rock on which all the buildings at the top stand. The Parthenon is the name of the main temple, the one that you can see from everywhere.

How to Get to the Acropolis

You can reach the entrance to the Acropolis by walking up one of the two approaches to the western end. The more atmospheric of the two is on the north side through the Plaka district where you will spot occasional hand-written signs directing you up through the steep and winding streets. Local shopkeepers are also used to being asked directions, as the route is not always obvious. The approach from the pedestrianised Dionysiou Areopagitou street to the south of the Acropolis is perfectly straightforward.

Evidence of a settlement on the southern slopes of the Acropolis dates the first habitation in Athens to about 3000 BC. The buildings that remain date mainly from the 5th century BC, when ancient Athens reached its pinnacle during the period that is referred to as the Golden Age of Pericles.

The Golden Age of Pericles

Pericles hired the finest workers of the day, including the master sculptor Phidias. He was the main artistic director of the Parthenon, which was the first building to be raised on the site. The great architect Iktinos (or Ictinus) was probably responsible for its overall design and construction.

It's now one of the well-known facts about the Parthenon that it has no straight lines in its construction, the apparent symmetry being created by gently tapering columns and steps. The building is designed using repeated ratios of 9:4, for such aspects as the gap between columns in relation to the width of a single column, or the width of the building in relation to its height.

The Goddess Athena

Originally, the focus of the building was a 40-foot-high (12 m) golden statue of the goddess Athena, after whom the city is named. A model of the Parthenon as it would have looked then, complete with golden statue, can be seen in the National Archaeological Museum.

The building took nine years to construct, was finished in 438 BC, and is made from marble quarried locally. To see how the marble was transported up to the top of the Acropolis, visit the Acropolis Museum. Flecks of iron in the chosen marble give the building its wonderfully warm golden glow in the evening light.

Several other buildings on top of the Acropolis are worth a closer look. To the right, soon after you enter, is the small temple of Athena Nike, added in 427-424 BC to celebrate victories by the Athenians in their wars with the Persians. Athena Nike means Athene of Victory, and yes, that's where the name of the trainers comes from.

The Parthenon was dedicated to a different aspect of the goddess, Athena Promachos, Athena the Champion. In 1686 the temple was destroyed by the Turks who were then occupying Greece. It has been reconstructed twice since then, most recently in 1936-1940.

The Turks wreaked havoc on the Acropolis, including building a mosque inside the Parthenon, which was left to fall into ruin before parts of it were sold off to Lord Elgin (see box below on the Parthenon Marbles). The Turks also used the building as a weaponry store, which resulted in further damage when the arsenal exploded after being fired upon. This happened in 1687 and removed the roof of the Parthenon.

Other Buildings

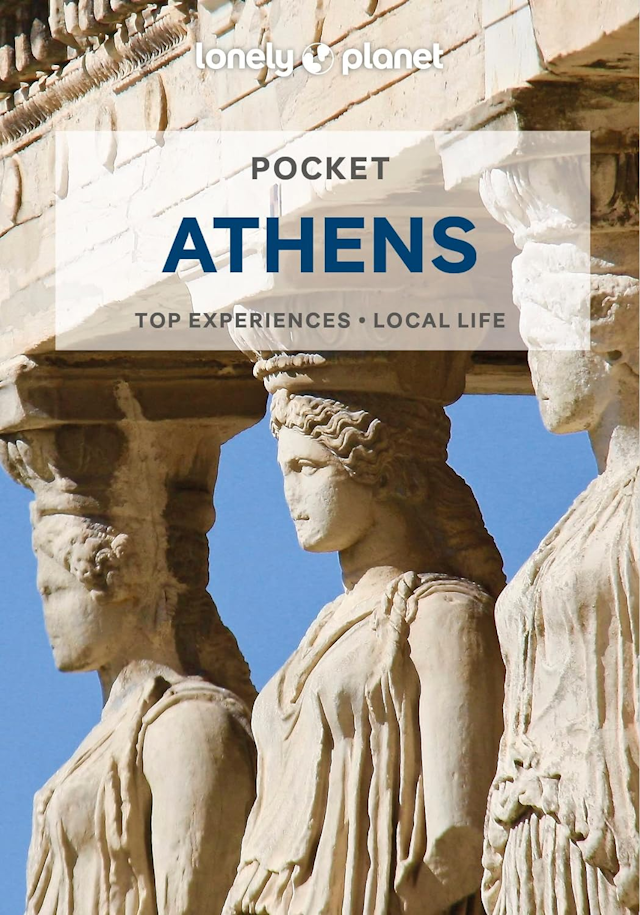

Over to your left as you approach the Parthenon from the entrance is the Erechtheion, added between 421 and 395 BC and partially reconstructed in 1827. It is said that the first olive tree in Athens sprouted on this spot when the goddess Athena touched the ground with her spear. An olive tree has been kept growing here since 1917 as a symbol of this legend.

This building includes the Porch of the Caryatids, where the supporting columns have been sculpted in the shapes of six maidens. Those you see today on the site are copies. Five of the originals are in the Acropolis Museum. The sixth was carried off by Lord Elgin.

The Parthenon Marbles

In 1801 Thomas Bruce, the Earl of Elgin, was the British Ambassador to the Porte, which was the name of the Turkish government that was then in control in Athens. The Turks were using antiquities from the crumbling Acropolis as building materials. Lord Elgin was allowed to save some stones and sculptures, which he ended up selling to the British government, who handed them to the British Museum in 1816. The most famous of these, the friezes from the Parthenon, became known in Britain as the Elgin Marbles, although the Greeks refer to them more appropriately as the Parthenon Marbles.

The Greeks have wanted the friezes back virtually ever since they gained their independence in 1832. Pressure was increased in the 1980s by the Greek Minister of Culture, Melina Mercouri, and the campaign continues. When the new Acropolis Museum opened in 2009, it had a special viewing area giving terrific views of the Acropolis and the Parthenon, and showing how wonderful the building would look if the friezes were returned. The British Museum had always argued that the friezes could not be returned because there was no suitable place in Athens where they could be safely displayed. That argument is no longer valid, but the friezes remain in London.

More Information

Don't miss this visual tour of Athens with photos by Donna Dailey of Greece Travel Secrets.

Latest Posts

-

Greek Air Traffic Controllers to Hold 24-hour Strike, Disrupting Flights on April 9

The Hellenic Air Traffic Controllers Union have announced a 24-hour strike for Wednesday, April 9, in response to the protest called by the Civil Servants’ Confederation (ADEDY). The strike is being h… -

Ten Best Budget Hotels on Santorini

Greece Travel Secrets picks the ten best budget hotels on Santorini, some with caldera views, some near beaches and some close to the heart of Fira. -

No Ferries in Greece on April 9 as Seamen Join Nationwide Strike

The Pan-Hellenic Seamen’s Federation (PNO) has announced its participation in the 24-hour strike called by the General Confederation of Greek Labor (GSEE) on Wednesday, April 9. The strike, which will… -

Karpathos: One of Europe’s Best-Kept Travel Secrets

The Greek island of Karpathos, a true hidden gem, has earned a spot on GEO magazine’s list of Europe’s nine best-kept travel secrets. -

Andros: Greece’s Top Hiking Island for 2025

Andros, named Greece’s top hiking island for 2025 by Conde Nast Traveler, boasts diverse landscapes, scenic trails, cultural charm and stunning beaches. -

Matt Damon and Christopher Nolan Arrive in Messinia to Start Filming “Odyssey” – First Images Released

A total of about 180 people arrived on two direct flights from Morocco, including actors as well as the core production team. -

Mavros Gatos: A Genuine Neighborhood Taverna Operating in Pangrati Since 1963

Among the many city eateries offering modern and classic Greek cuisine, Mavros Gatos in Pangrati stands out as a prime example of what a true traditional taverna should be today. -

Ten Best Dishes in Greece

Greece Travel Secrets lists the ten best dishes to try in Greece, especially if it’s your first visit, and also discover the best places to find them. -

Athens’ Most Coveted Culinary Hotspots

Athens sizzles with culinary creativity, blending timeless classics and innovative flavors at unforgettable dining spots. -

Culture Ministry Announces Free Admission to Greek Museums and Sites

Greece’s public museums and archaeological sites will offer free entry on Sunday, March 2, and Thursday, March 6, following a decision by the Greek Culture Ministry. According to the ministry, on the…